Human Connection

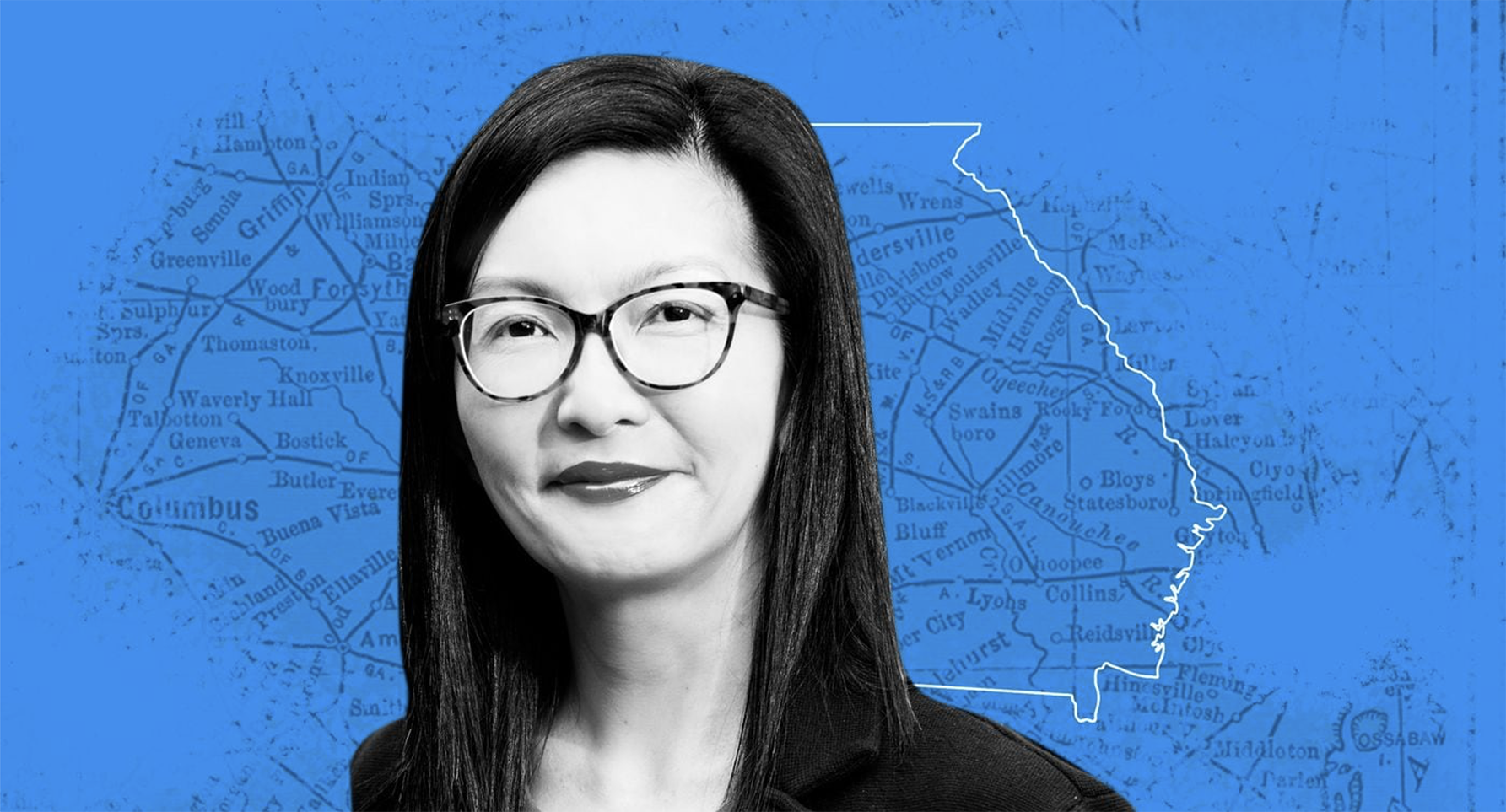

One of the biggest challenges anesthesiologist Michelle Au, MD, MPH faces on the front lines of the COVID-19 pandemic is continuing to offer personal, warm care to her patients.

“Unfortunately, the highly infectious nature of the coronavirus has changed the fundamental way we relate to, and take care of, our patients,” said Dr. Au. “For infection control purposes, we must be masked and gloved and talk to patients at a distance, or even through baby monitors. But if we are to truly care for the body and spirit of sick, frightened patients who are unable to have their family with them, we must Rnd ways to foster and convey the human connection, which is fundamental to the practice of heath care.”

Being Part of a Community

Being a front line physician during a generational public health crisis gave Dr. Au a powerful reminder of the awesome social responsibility physicians face every day, even outside of the four walls of their hospitals or offices.

“Beyond providing medical care to patients, we are community leaders. People look to us for answers and for reassurance. We are educators, using our decades of scientific training and clinical experience to break down complex concepts, such as this virus. We are scholars, keeping abreast of rapidly changing research and best practices. And we are role models, showing, rather than telling what those best practices should be, knowing that our communities are looking to us to help guide the way.”

But community goes both ways. During the early days of the pandemic, Dr. Au and her colleagues appreciated the support of their community as they coped with a surge of very sick patients. They received supportive cards and emails, in addition to donated supplies and meals during their shifts. “While we were the ones on the front line, it was heart-warming and bolstering to know that there was a whole community right behind us, helping us to do our jobs.”

Balancing Personal and Professional Responsibilities

As the mother of three young children, Dr. Au was understandably concerned that she could be putting her family at risk by bringing home the virus.

“Diminishing clinically excellent, compassionate care to my patients was never an option, so I continue to practice, but I have made changes to many of the routines around our home. For example, to reduce risk to my family, I sequester myself when I get home until I’ve showered and changed. I take pains to separate my family from anything that has been exposed to the hospital environment and we do exercise an additional degree of separation from casual, close social contact even in everyday life, out of a surfeit of caution.”

When asked if a career in medicine was more diScult than she expected, Dr. Au says, “We didn’t choose to become doctors because it would be easy. We chose to become doctors because the work we do gives our lives purpose, even when it’s hard.”

Certified by the American Board of Anesthesiology, Dr. Au is an anesthesiologist at Physician Specialists in Anesthesia, a provider of adult anesthesiology services within the Atlanta health care community. (Published: October 5, 2020)

Tammi Brown, Chatham County Health Department Nurse Manager, was among the first in Georgia to receive the vaccine against COVID-19 on December 15, 2020 as Memorial University Medical Center emergency room nurse David Wilson awaits another dose and Gov. Brian Kemp and State Sen. Ben Watson look on.

Tammi Brown, Chatham County Health Department Nurse Manager, was among the first in Georgia to receive the vaccine against COVID-19 on December 15, 2020 as Memorial University Medical Center emergency room nurse David Wilson awaits another dose and Gov. Brian Kemp and State Sen. Ben Watson look on.