State lawmaker, physician says doing so would help restore voters’ faith and improve health outcomes here. These days, it’s easy for politics to make you cynical. Especially in this hyperpolarized era, during an election year, in the heart of the No. 1 battleground state in the nation, it does seem at times like partisan views […]

By Amy Yee ’96Illustrations by Nicole XuFall 2021 A memory from the start of the COVID-19 pandemic remains indelible. It was early March 2020, and schools and businesses were yet to close down. But already a gnawing sense of foreboding loomed, apart from the virus itself. My fears were confirmed by a LinkedIn post from […]

Ways to boost Ga.’s vaccination rate

With only four in ten Georgians fully vaccinated against the virus, and a new school year upon us as the delta variant continues its relentless blitz through our population, there has never been more urgency to protect our communities from further illness, injury, and death by taking bold moves to help more of our population get vaccinated.

Yet in a press conference last month, Gov. Brian Kemp, while acknowledging the importance of statewide vaccination, seemed to have all but given up on any further efforts to reach the eligible Georgians who remain unprotected.

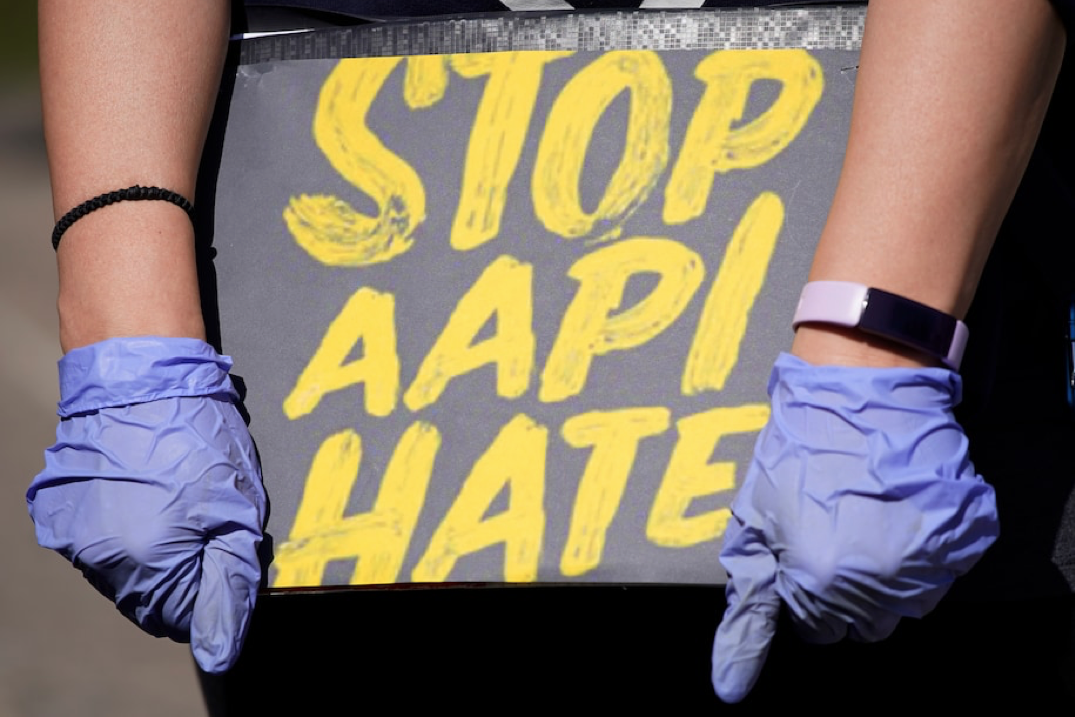

Opinion: How to investigate the lab-leak theory without inflaming anti-Asian hate

A woman holds a sign supporting an end to hate directed at Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI), as seen at the Logan Square Monument in Chicago on March 20. (Nam Y. Huh/AP)

By Leana S. Wen

June 1, 2021 at 4:05 p.m. EDT

Universal pre-K is not government overreach or massive subsidy

In a guest column, state Sen. Michelle Au, D-Johns Creek, applauds the push by President Joe Biden for universial pre-K.

In his first formal address to Congress five days ago, Biden said, “The great universities in this country have conducted studies over the last 10 years. It shows that adding two years of universal, high-quality preschool for every 3-year-old and 4-year-old, no matter what background they come from, puts them in the position of being able to compete all the way through 12 years and increases exponentially their prospect of graduating and going on beyond graduation.”

Investments in early childhood programs not only improve outcomes for the children who participate but for Georgia and the nation as a whole, says Au.

By Dr. Michelle Au

Perhaps the most surprising thing about President Biden’s call for universal pre-K in his American Families Plan is that anyone is surprised at all. Universal pre-K — that is to say, broad access to quality preschool education — is the norm in most wealthy nations.

Op-Ed: Fight the gun violence epidemic like we fight cancer — one small step at a time

APRIL 14, 2021 11:14 AM PT

With only four in ten Georgians fully vaccinated against the virus, and a new school year upon us as the delta variant continues its relentless blitz through our population, there has never been more urgency to protect our communities from further illness, injury, and death by taking bold moves to help more of our population get vaccinated.

Yet in a press conference last month, Gov. Brian Kemp, while acknowledging the importance of statewide vaccination, seemed to have all but given up on any further efforts to reach the eligible Georgians who remain unprotected.

Opinion: Georgia Republicans were quiet about their attack on voting rights, but, oh, did they laugh

People wait in line for early voting at the Bell Auditorium in Augusta, Ga., on Oct. 12.

(Michael Holahan/The Augusta Chronicle via AP)

By Michelle Au

March 27, 2021 at 11:06 a.m. EDT

Michelle Au, a Democrat, is a Georgia state senator.

What struck me the most was the noise coming from all the wrong places.

This hastily sewn-together bill is a broad attack on voting rights. It includes imposing limits on the use of mobile polling places and drop boxes; raising voter identification requirements for casting absentee ballots; barring state officials from mailing unsolicited absentee ballots to voters; and preventing voter mobilization groups from sending absentee ballot applications to voters or returning their completed applications. The list goes on.

The Thing with Feathers

By Michelle Au ’99

Endnote, Spring 2020

Last spring my family found a bird’s nest in our garage. We noticed it by chance, high on a shelf 10 feet up, a packed swirl of twigs and pine straw about the size and shape of a catcher’s mitt. One of my kids had broken a window in our garage months before (to this day, both the projectile and culprit remain at large) and it must have been through this breach that the bird gained access. It was unclear how long the nest had been there—for all I knew, it could have been months and I’d just never noticed it. We have a way of walking right past things we don’t expect to see.

Though she was rarely sighted, we were further surprised one day to find our mysterious tenant had delivered a clutch of five Instagram-worthy speckled eggs. We cooed and marveled over this development, but when nothing happened after a few weeks, we figured the eggs had either been abandoned, or else were duds.

Au for Georgia, Inc.

5805 State Bridge Road, Suite G238

Johns Creek, Georgia 30097